From antiquity to early Christianity

Some people refer to antisemitism as the “oldest form of hate”. While there might be other forms of hatred that pre-date it, there is no doubt that antisemitism is one of the of the oldest. Historians have demonstrated that it reaches back into antiquity, with many examples drawn from across the ancient world: in Egyptian, Mesopotamian, and Greco-Roman societies.

Examples of ancient antisemitism were much like any other xenophobic incidents from the time: usually a result of rivalries between warring nations and groups, professing the superiority of their god(s) over that of their neighbours.

Yet, one of the most important factors in the development of anti-Jewish bigotry was the spread of Christianity. This came with the idea that Jewish people and their “special relationship” with God, as established by the Mosaic Covenant – which was believed to be spoken to Moses on Mount Sinai – had been superseded by a new covenant through Jesus.

The rise of Christianity

Christianity originally developed as one of many sects of Roman-era Judaism in the ancient Land of Israel. During this time, disagreements between Jewish followers of Jesus and other Jews were not uncommon. It was not until Christianity evolved into its own religion, separate from Judaism, that Jews came to be seen as the primary enemy. As Christianity developed into a religion, its Jewish origins were often erased and forgotten. Even the fact that Jesus and his Apostles lived as practising Jews, immersed in the traditions and teachings of the culture that has since come to be known as Judaism, was overlooked or in the worst cases denied.

The adoption of Christianity as the state religion of the Roman Empire during the reign of Constantine in the fourth century CE, meant that Jews, who had previously been one among many of the Empire’s subjugated (and at times rebellious) peoples, would become a binary non-Christian ‘Other’. Many of the negative Jewish stereotypes that we see today are derived from the New Testament and the teachings of early Church fathers (such as Augustine of Hippo and John Chrystostom).

Christian hatred toward Jews of this era centred on the mistaken belief that the Jews (and not the Romans) were responsible for the death of Jesus, a sin ( deicide ) for which they and their descendants were to suffer for all eternity – though not to be killed, but instead left as a warning to Christians. According to Christians of the time, it was only by accepting Jesus as the Messiah that Jews be saved. Some did accept Jesus. But the fact that many refused to do so became another bone of contention for Christians. This led to stereotypes that Jews were clannish and stubborn and gave rise to the belief that God had forsaken the Jews in favour of Christians.

The Medieval period

Many of these negative stereotypes associated with Jews and Judaism developed as Christianity spread across Europe during the Medieval period. The stereotypical hook-nosed Jewish banker that has appeared in numerous forms of popular culture, for example, finds his origins in Medieval depictions of both Jews and the Devil.

This widespread Medieval association between the Jews and the Devil originates from The Gospel According to John, in which Jesus chastises a group of Jews for being the children of the Devil, rather than those of God (John 8:44-47).

Also, as Jews were banned from participating as members of guilds across much of Christian Europe during the Medieval and Early Modern periods, one of the few trades in which they were permitted to engage was moneylending. The Church forbade Christians from engaging in the practice of usury – the act of lending money at high rates of interest – but permitted it for Jews. This resulted in Jews being able to make a livelihood when other avenues were closed to them, but it also angered Christians, strengthening the racist association between Jews and money.

While a long association in the moneylending and currency exchange trades may have helped a select number of Jewish families to amass greater wealth, the vast majority of European Jewry lived in poverty, alongside their Christian counterparts.

While many Church leaders today reject ancient religious racism against Jewish people, this association lives on in even the most secular of societies in conspiracy theories that link Jewish people with all manner of problems plaguing humanity.

Forced conversions, expulsions and violence

For most people today the Holocaust stands out as the most lethal episode in Jewish history. Yet it’s important to remember that Adolf Hitler and the Nazi party did not invent antisemitism, discriminatory policies, or persecution.

In fact, beyond their use of mechanised murder, their attitudes towards Jewish people were the fruits of centuries-long lethal persecution that the late Holocaust historian Raul Hilberg (1926–2007) summarises as ‘conversion, expulsion, annihilation’.[1]

Throughout the Medieval period, Church leaders in Europe often forced Jewish people to convert to Christianity under threat of death. This was based on the belief that the Christian Church had replaced the special relationship between the Jews and God.

Forced conversions were typically accompanied by outbursts of mob violence sometimes instigated by the authorities as a way of distracting disaffected subjects, sometimes enacted by the subjects themselves – events that would later come to be described as ‘ pogroms ’ during the nineteenth century. During the Medieval period, these violent outbursts were a common occurrence during Christian holy days, when local priests whipped their flocks into frenzied mobs to enact revenge on their Jewish neighbours for the alleged crime of deicide against Jesus.

One of the most lethal examples took place in 1095, when Pope Urban II preached a Crusade to ‘liberate’ the ‘Holy Land’ from Muslim rulers. In the hysteria that ensued, Jewish communities along the Rhine and Danube were massacred by Crusaders on their way to Jerusalem. Such massacres were a common feature of all subsequent Crusades. Other accusations levelled against Jews for which they suffered violence were the ritual murder of Christians (the notorious blood libel ), the poisoning of wells and other sources of water, and desecration of the Host . These false accusations and resulting bloodshed were a common occurrence throughout Europe over the centuries.

Even during periods of relative peace, European Jews were subjected to various forms of discrimination. Living precariously as outsiders, at the whim of local rulers, Jewish communities were subject to humiliating treatment, violence, forced conversions and sporadic expulsion from their homes and communities. Jewish people were often denied entry into certain trades and professions.

To earn a living, many Jewish people had little choice but to work in commerce, moneylending, or currency exchange. Most of these commercial endeavours were small scale, but contributed to the rise of hateful tropes and stereotypes.

Money was not the only way anti-Jewish hatred manifested over the centuries. Until their emancipation during the course of the nineteenth century, when they were granted the same citizenship and rights as their non-Jewish counterparts, Jews in Europe were forbidden from owning property, living, and working in certain cities and towns, attending institutions of higher learning, and serving in the military. Jews were often confined to designated streets that were known as the Judengasse “Jewish street” or ghetto.

The word ‘ghetto’ is derived from the Italian word for ‘foundry’ and in its use in describing an area designated for Jewish residence has its origins in the notorious Venetian Ghetto. Established during the sixteenth century, the Ghetto housed Venice’s Jewish population and served to isolate them from the city’s Christians. While Venetian Jews were liberated from the Ghetto at the end of the eighteenth century, the word ‘ghetto’ would continue to be used to describe urban areas of Jewish residence. While the origins of the term are negative, it took on further negative connotations during the Holocaust when it was used to describe the overcrowded and unsanitary quarters in which the Nazis forced Jews to live in areas under German occupation.

One of the ways Jews were historically persecuted was to single them out for humiliation and social exclusion. This may have manifested itself in being forced to walk in the gutters rather than paved streets, being forced to tip their hats to Christian passersby, or being forced to ride donkeys instead of horses to indicate their lowly status in some Muslim societies. One way in which it was possible to identify Jewish communities for such treatment was through forcing them to wear degrading clothing and accessories. This practice originated in the Islamic world under the Umayyad Caliphate in the early eighth century and was reinforced a century later in 850 CE by the Abbasid Caliph Al-Mutawakkil (822–861), who decreed all Jews must wear yellow garments and patches on their hats and sleeves to distinguish them from Muslims.

Depiction of a Jewish man, 1600s, wearing the yellow Jewish badge on his cloak.

This practice would make its way to Christian Europe. At the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215, Pope Innocent III (1161–1216) decreed that all Jews living in Church-controlled lands must dress in distinguishing attire. This ruling was refined in 1227 at the Synod of Narbonne where it was decreed that all Jews must wear an oval badge of very specific measurement on the breast of their garments. This practice would spread throughout Europe over the ensuing decades with variations to the shape and colour of the required badge or sometimes hat. Yellow was one of the most common colours decreed for this purpose; a colour that would come to be associated with negative characteristics such as treachery, dishonesty and immorality.

The practice of policing Jewish clothing fell away during the Early Modern Period, until 1941 when it was revived by the Nazis and their collaborators across Axis-occupied Europe. During this time, Jews were forced to wear stigmatising badges or armbands. The most prevalent manifestation was the notorious Judenstern, a yellow, six-pointed cloth star to be affixed to the outer garments of Jewish people over the age of six whenever appearing in public. Such practices would ultimately make it far easier for the Nazis and their collaborators to gather Jewish people for concentration in ghettos and for deportation to labour and extermination camps.

Expulsions and uprisings

When forced conversion failed, Church leaders and other authorities often resorted to expelling the Jews from their domains. While there were certainly examples of Jewish expulsions in the ancient world and in early Christian societies, wide-scale expulsions became more common in Christian Europe from the eleventh century onwards. Many of the expulsions of Jews from western Europe from this time – especially from England and what is now France and Germany – resulted in significant waves of Jewish migration into Poland, a land seen at the time as being tolerant of and even favourable towards Jewish people.

Poland became the main centre of Jewish life in Europe before the Holocaust and contributed to the myth that most if not all Jews have Polish origins. Poland’s tolerant nature was, however, fleeting and in time its Jews – like others across the continent – were also subject to the same persecution as their fellow Jews in western Europe, especially in times of social and political unrest.

Expulsion from Spain

Arguably the most famous expulsion of Jews in European history took place on the Iberian Peninsula at the end of the fifteenth century. In 1492, the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile issued an edict known as the Alhambra Decree ordering the expulsion of all practising Jews and Muslims from Spain. The decree was issued in the wake of the Reconquista – the Catholic reconquering of the Iberian Peninsula from Muslim rulers – and was a way to expunge non-Catholic elements and influences on the Spanish population and consolidate Catholic control. To avoid expulsion and further persecution, many Jews chose to convert to Catholicism. Those who did not were forced to leave Spain by the end of July 1492. These Jews are estimated to have numbered between 40,000 and 100,000 and were known as Sephardim (from the Hebrew word for Spain, Sepharad). They left Spanish lands, settling in Portugal, but were expelled again only four years later in 1496, and in 1497, many were forced to convert to Catholicism. Many would make their way to southern France, parts of central and northern Europe and, overwhelmingly, North Africa and the Middle East. The expulsion and dispersion of Sephardi Jews was a significant event in Jewish history and community memory. Yet, like the forced conversions and bloody massacres, it was just one of many such incidents across Europe.

The Khmelnytsky Uprising

One of the most prominent massacres of Jews to occur in Europe prior to the Holocaust took place in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth during the Khmelnytsky Uprising (1648–1657). Tens of thousands of Jews were slaughtered by bands of rioting Cossacks, Crimean Tatars and Ukrainian peasants. The uprising, led by Ruthenian nobleman Bohdan Khmelnytsky (1595–1657), occurred in the Commonwealth’s eastern territories (roughly corresponding to the borders of present-day Ukraine) and was directed at the Polish-Lithuanian crown, aristocracy, and magnates. Jewish communities, however, were caught in the crossfire. During the period of the Commonwealth’s existence, many members of the aristocracy and magnates left their estates under the management of Jewish leaseholders who were responsible for collecting taxes and rent from tenants. Jews were massacred as the uprising made its way across the eastern part of the Commonwealth. The rioters, influenced by centuries of existing anti-Jewish sentiment, mistakenly perceived all Jews to be agents of the Polish-Lithuanian ruling classes. The exact number of Jewish people murdered during this time is unknown and historians are still debating its extent. The Khmelnytsky Uprising is widely considered the largest massacre of Jews until the Holocaust, and its leader, Bohdan Khmelnytsky, is seen as one of the greatest villains of Jewish history prior to Adolf Hitler.

Antisemitism as an ideology

While hatred and persecution of Jews has existed for as long as there have been Jewish people, much of the historic vitriol targeted Jews for their religious difference. You would think that by converting to Christianity, a Jewish person could be protected from persecution, but things weren’t always so simple.

During the Spanish Inquisition, even though many Spanish Jews had converted to Catholicism to avoid expulsion, these ‘New Christians’ continued to be suspected of remaining loyal to Judaism and were often subjected to persecution. In this context, the idea of ‘blood purity’ became an obsession within a Catholic society concerned with uncovering hidden Jewish influences. This idea has resurfaced time and again throughout history, most notably in Nazi Germany with the introduction of the 1935 Nuremberg Laws . Over time, hatred against Jewish people continued to evolve and take on a different character, less concerned with Judaism as a religious tradition, particularly in the context of the Enlightenment and the later development of national movements across Europe. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, questions about Jews’ place in society would plague European thinkers, writers, politicians, and average civilians. People of the time questioned whether Jewish people could even be considered part of their nations if they identified as Jewish and practised their faith.

Assimilation

The French revolutionary Count Stanislas de Clermont-Tonnerre (1747–1792) declared to the French National Assembly in 1789, ‘Jews should be denied everything as a nation, but granted everything as individuals’. During this era, it was the belief that it was only by relinquishing ties to the Jewish community and embracing the dominant national culture in full, could a Jewish person be considered a true loyal citizen. In this context, Jews – both individuals and communal organisations – developed different strategies for integrating into society.

Many jumped at the chance and threw themselves wholeheartedly into emerging national movements, identifying as Germans, French, Italians or Poles ‘of the Mosaic faith’ – a form of acculturation whereby they were able to identify with both the dominant national culture and their Jewish heritage. In this context, to be a good Jew was first and foremost to be loyal to one’s country, as rabbis across Europe urged their congregants. For others, embracing the dominant national identity and culture was not enough, and many converted to the dominant local Christian denominations as a means of more fully integrating themselves into society – a phenomenon known as assimilation.

Depiction of Napoleon emancipating French Jews. 1806. Courtesy Bibliothèque nationale de France.

For many – both those abandoning Judaism in favour of Christian denominations and those satisfied with remaining Jewish – it was hoped that anti-Jewish prejudice would disappear. Yet, as Jews began to integrate into their wider societies and were emancipated over the course of the nineteenth century, Jew-hatred evolved as well.

As most Jews no longer dressed differently from non-Jews, and adopted the dominant language and culture of the nations in which they lived, anti-Jewish bigots required a new model of separating Jews from the rest of the population. ‘Antisemitism’ as a racialised hatred of Jews evolved during a period of immense societal and cultural change.

Racist pseudo-science

As the French Jewish philosopher Alain Finkielkraut famously claimed, antisemitism ‘turned racist only on the fateful day when, as a consequence of Emancipation, you could no longer pick Jews out of the crowd at first glance.’[2] Taking advantage of the continent-wide struggles for national identity as well as emerging pseudo-scientific theories on race, xenophobes attempted to justify their anti-Jewish prejudice as one rooted in ‘science’ and therefore one of legitimacy, rather than religious intolerance. Antisemitism took on a stronger racial connotation that presented Jews as biologically irreconcilable to the European, non-Jewish people around them, and this was something that conversion and assimilation would never be able to fix.

Antisemitism as a new cultural and political ideology only emerged in the last third of the nineteenth century. The term ‘antisemitic’ (German: antisemitisch) was first used in 1860 by the Austrian Jewish scholar Moritz Steinschneider (1816–1907) to criticise the French philosopher Ernest Renan (1823–1892) for his anti-Jewish views. The term is derived from the idea that Jews were part of a so-called ‘semitic’ race. In fact, the term ‘semitic’ refers to a group of languages which includes Hebrew, Arabic, Aramaic, Syriac, and not to ethnic groups.

Yet, it was not for another decade or so that the term ‘antisemitism’ was popularised when the German journalist and self-proclaimed antisemite Wilhelm Marr (1819–1904) founded the League of Antisemites (German: Antisemiten-Liga) with the desired goal of once again excluding Jews from German society, reversing the process of emancipation, and combating the supposed detrimental influence of Jews on wider society.

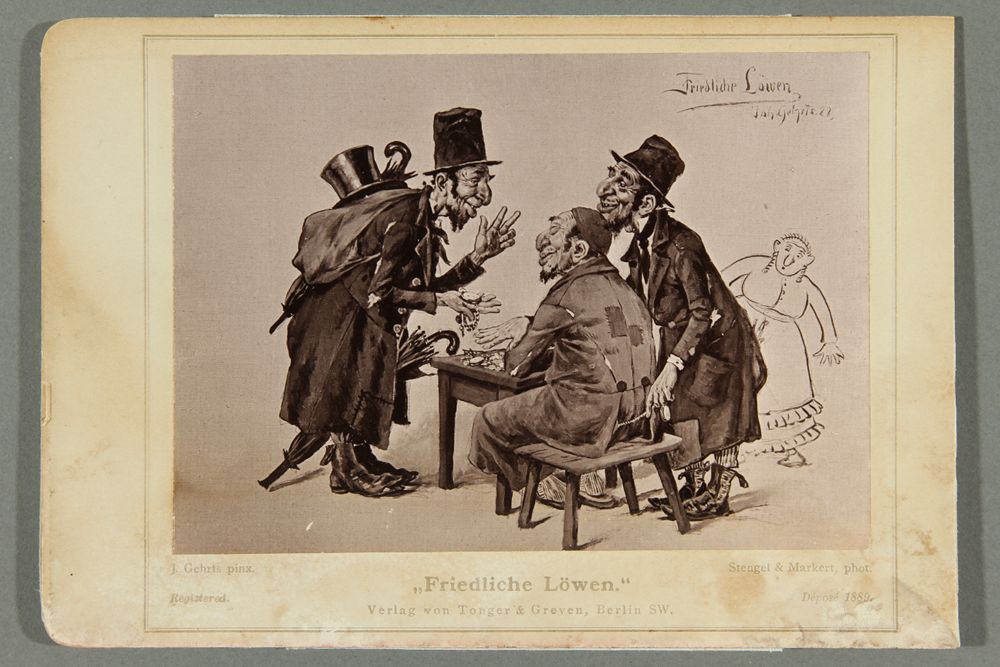

Antisemitic German postcard reproduction of a painting by J. Gehrts produced in late 19th-century Berlin. Courtesy United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

The idea of a racial threat posed by Jews and the ideology of antisemitism were not exclusive to Germany and took root in other societies in Europe and further afield. The ‘new’ antisemitism made use of many of the age-old religious tropes. For example, the murder of Christ manifested in the non-religious accusation of Jewish treachery and willingness to betray one's country to enemies (an accusation that frequently occurred during times of war); the poisoning of wells and sources of water manifested itself in accusations that Jews, particularly immigrant Jews, were responsible for the spread of disease as well as radical political ideologies including Anarchism, Communism and Socialism; and tropes about Jews and money persisted as Jews were accused of hoarding wealth and controlling world finances. But finances were not the only thing that antisemites accused Jews of controlling.

Same myths, new conspiracies

In 1903, the Russian newspaper Znamya (The Banner) serialised a text alleging to be a secret plan for Jewish world domination, in which the so-called Elders of Zion set out how this would be achieved through seizing the financial markets, political and legal systems, real estate, and the spread of Liberalism though the media. The text, published in full in 1905 as The Protocols of the Meetings of the Learned Elders of Zion, was found to be a complete forgery, plagiarised from numerous early texts, including a novel by the German antisemite Hermann Goedsche and a political satire (with no relation to Jewish themes) by French attorney Maurice Joly. It was widely discredited from as early as 1921. It should be remembered that at the time of the Protocols publication, the Russian Empire was home to the world’s largest Jewish population. And yet, Russian Jewry lived without many of the rights and freedoms won by their counterparts in western and central Europe over the course of the nineteenth century and were subject to numerous restrictions and widespread persecution including regular government-incited pogroms. They were wholly without capacity for the levels of control the Protocols claimed Jews possessed.

From Russia, the text was spread to other parts of the world, particularly by monarchists and others fleeing the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, where it gained traction in societies as diverse as the United States of America (further disseminated there by the automobile industrialist Henry Ford), Germany (where Adolf Hitler cited it as one of the key texts inspiring his antisemitism), and even Japan. The Protocols continue to remain influential today in certain societies and are widely available from major book distributors. There is a clear link between the Protocols and contemporary conspiracy theories claiming Jews control Wall Street, Jews are responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, or that the United States of America is a puppet of the State of Israel.

In the same way that antisemitism evolved as a racialised prejudice influenced by emerging ideas about race and biology prevalent in the West, it mutated and was further influenced by other emerging modern political, cultural, and class-based ideologies.

Jews and Communism

Communism, for example, has long been held by some of its opponents to be a product of modern Judaism. In part, this belief was influenced by the fact that one of its central figures, Karl Marx, was of Jewish ancestry, even though in his writings and public lectures, Marx himself peddled antisemitic tropes.

Further, as Communism’s influence spread, many of its participants and some leaders were Jewish. But just as some Jews were drawn to Communism for its promise of a just and more humane society, so too were many people of other ethnic, religious and cultural backgrounds. Nevertheless, the Jewish ancestry of some prominent Soviet leaders contributed to the myth of Judeo-Bolshevism, which spread across the West.

This is not to say that Jews living in Communist societies did not suffer persecution. Antisemitism is a very effective and malleable tool that is often recast to suit the context. While antisemites in the West were fixated on the imagined threat of Judeo-Bolshevism, for antisemites in the USSR Zionism would serve as the manifestation of a threat of Jewish world domination.

In this paradigm, Jews were presented as agents of the State of Israel seeking to overthrow the world order. This Soviet anti-Zionism was originally disseminated alongside a general antipathy to the Jewish religion, as a means of transforming Jews into good Soviets. It then took on many of the notorious antisemitic stereotypes and tropes that had developed over the centuries in different contexts, including the blood libel and aspects of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

Nazi propaganda poster with the floating head of a sinister, caricatured Jew as the puppet master for international Jewry, watching two cartoonlike figures, John Bull, for England, and Stalin for the Soviet Union, shaking hands over a map of Europe. 1942. Courtesy United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Soviet anti-Zionism gained traction outside of the USSR, for example influencing the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 3379 of November 1975 that determined Zionism as a form of racism. This was revoked by Resolution 46/86 in 1991. Nonetheless, the Soviet misrepresentation of Zionism has continued into the present day.

Post-Holocaust antisemitism

Antisemitism has always been an ally to unstable situations, whether political, economic or cultural. It is no surprise that during the Second World War, Nazi Germany found eager participants in their persecution of Europe’s Jews among the populations of territories that came under their direct and indirect control.

Antisemitism did not end with the Holocaust. As survivors emerged from hiding or were liberated from the camps and attempted to rebuild their lives, many were confronted with the fact that antisemitism remained.

For some survivors, returning to their former homes brought additional trauma. At best, they were met with a cool reception from former friends and neighbours, in worse cases with acts of violence for daring to return. One example of such violence occurred in Kielce, Poland in 1946, where forty-two Jews were murdered, and others injured in a resurgence of the blood libel. Nor was antisemitism confined to Europe. Many Jews living in the Middle East and North Africa were similarly confronted and impacted by the rise in nationalism that was exacerbated after the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. This resulted in the expulsion and flight of 850,000 Jews from lands in which they had lived for thousands of years. Even those survivors who left Europe and the Middle East for countries such as the United States of America, Canada, Argentina or Australia, did not find societies entirely free of antisemitism. In many English-speaking countries, a soft form of antisemitism persisted, where Jews continued to be prohibited from joining certain country or golf clubs, hotels denied accommodation to Jewish guests, and many businesses and elite universities, particularly in the USA, maintained unofficial policies that prevented the hiring of Jewish employees, or admission of Jewish students.

Antisemitism today

As the horrors of the Holocaust became known throughout the world in the decades after the end of the Second World War, many expressions of overt antisemitism would be seen as taboo, particularly in a world growing more conscious of anti-racism, gender and sexual equality, disability rights, and a respect and acceptance of difference in general. As a result, antisemitism became less visible.

Yet, prejudice toward Jews continues to exist throughout the world. In a way, the extent of the barbarity that took place during the Holocaust has dulled our senses when it comes to identifying subtle antisemitism. Overt and often violent expressions of antisemitism from neo-Nazis and other white nationalists or religious extremists are easy to identify and condemn. But it is the subtle or covert acts of prejudice that make use of age-old antisemitic tropes, that show the extent to which antisemitism has been normalised in Australia, and around the world.

Antisemitism is just plain and simple racism. While it’s a particularly old and deeply pervasive form of it, we need to ensure we call it out for what it is.

[1] Raul Hilberg, The Destruction of the European Jews (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1961), 3.

[2] Alain Finkielkraut, The Imaginary Jew, trans. Kevin O’Neill and David Suchoff (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1994), 83.